Science of the Comstock - Tour

Home | Tour | Physics | Chemistry | Earth Science | Environment | Scams | Lesson Plans

Tour Topics:

Introduction

Mining Tour

QTVR

Vocabulary

Mining Tour

Introduction

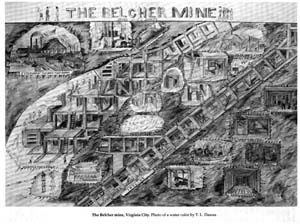

Mining in Virginia City, Nevada used traditional practices, but also required several innovations that were then taken to other mines throughout the world. Mining consists of taking rocks that contain minerals of interest out of the ground. Here, the minerals of interest in the rocks contained silver and gold. The problem the miners had to solve was getting the largest quantity of the silver and gold while taking out the least amount of rock that contained little or no silver or gold (waste rock). They had to do this while maintaining relatively safe working conditions yet work quickly. The conditions that were considered safe back in the late 1800s would not be considered safe today, so to modern miners, the procedures and conditions of mining may look unsafe. A photograph of a painting (included by permission of the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, NBMG) of the Belcher Mine shows many of the mining steps (taken from Tingley, J.V., Horton, R.C., and Lincoln, F.C., Outlines of Nevada Mining History, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication 15, University of Nevada, 1993, p. 13). The picture is quite large, and can take a long time to load.

larger version of image

Prospecting

Of course, first the prospectors had to find something to mine. The prospectors looked for rocks they had seen associated with gold in other situations. In Virginia City, most of the prospectors were returning from the California gold rush, so they had in mind a particular type of rock that contained gold. The first discovery in the area was made by Abner Blackburn near the present site of Dayton in July 1849. Prospectors and placer miners followed the traces of gold up the canyons until in 1859, the Comstock Lode was discovered. Once the prospectors found a likely area and rock type, the prospectors would dig out some rock and pan it to see if they could see gold flecks staying behind in their gold pan. Panning is a quick and primitive way of assaying the rocks for gold based on the fact that gold is denser than rock, so the rock will be washed out with water and the gold will be left behind in the bottom of the pan.

This photograph points out some of the many prospects on a hill on the northwest side of Virginia City.

Possible Ore Rocks

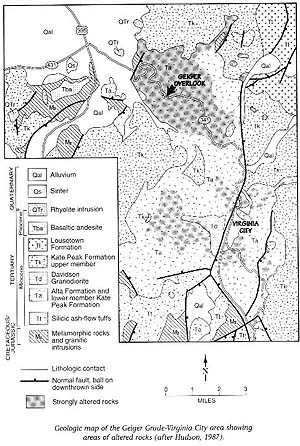

The rock the prospectors saw near Virginia City was a rock (hydrothermally altered) that had turned white and red from hot waters that had washed through the rocks about 14 million years ago. This photograph from the road over the Virginia Range to Virginia City, the Geiger Grade, shows such hydrothermally altered rocks. This modern map of the geology of the area around Virginia City, used by permission of the NBMG (Purkey, B.W. and Garside, L.J., Geologic and Natural History Tours in the Reno Area, NBMG Special Publication 19, University of Nevada, 1995), shows the heavily altered rocks in a large stippling.

The hot waters that wash through the rocks can carry precious metals dissolved out of the rocks in the surrounding area. The hot waters lose these precious metals from the solution when conditions of the rocks through which the waters are moving change. The temperature can drop, or the rock type can promote the precipitation of the metal either as a compound (often with sulfur) or by reducing the metal in solution to the free metal. As discussed in the Chemistry section of Ore Processing, silver was generally combined with sulfur in the Virginia City ores. In this way, precious metals that were scattered throughout the rocks were concentrated in an ore deposit. The deposit at Virginia City was called the Comstock Lode.

larger version of image

Moving the Ore Rocks Out of a Mine

Starting a Mine

Once the prospector thought he had found some ore, he usually needed to convince somebody to buy the prospect in order to mine the difficult ore and move the large volumes of material. In Virginia City, a single man could not mine the deep ore and remove enough ore to make a living. In order to convince a company to buy the prospect, the miner had to have evidence of the quality of the ore, so he had rocks from his prospect assayed.

Getting to the Ore

Once a company had bought the prospect, large scale mining began. In Virginia City, people and companies came quickly. By 1862, 80 mills were in operation, only 3 years after the discovery of the Comstock Lode. The population in Nevada increased so it could become a state in 1864.

Miners followed a vein of rock that was high in the precious metal.

The miners often entered their mine through adits, horizontal tunnels from the surface, shown in these pictures covered over with doors. They removed the rock with the metal and took only as much rock that didn't have the metal as was necessary to follow the vein. To move the rock, large equipment had to be brought in. The tunnels that went horizontally into the mine (called adits) were often dug to provide access to the tunnels that followed the veins (drifts).

Taking the Ore to the Surface

This diagram, used by permission from the NBMG, summarizes some mining techniques used on the Comstock, but also in other underground mines. (From Purkey and Garside, p. 58.)

Head Frame

Vertical tunnels, shafts, were dug in order to haul the rock to the surface and often to deliver men and equipment to the work site. The system for hauling the rocks up the shaft involved the construction of a "head frame" that consisted of a large wheel at the top to change direction of the cable pulling up the bucket, and a winding wheel onto which the cable was wound. This is a photograph of the New York mine headframe in Silver City on the Comstock, built in 1913.

The cable to lift the ore carts and buckets was developed by Andrew S. Hallidie of San Francisco in 1863. He went on to use his cable development skills for other applications, notably the San Francisco Cable Cars.

Ore Carts and Tracks

Iron tracks for mining carts to carry the rocks were installed on horizontal (or relatively horizontal) tunnels. Until modern combustion engines were invented, the ore carts were pulled by donkeys or mules, or they were pushed by men. This photograph (used by permission of NBMG) from Outlines of Nevada Mining History (Tingley, Horton, and Lincoln, p. 15) shows the interior of the Gould and Curry mine with miners and ore carts in the early 1880s.

Chutes were built so the rocks could be moved from one level to another and onto the ore buckets that were pulled up from the mine. This photograph of a model in the Nevada State Museum (used by permission of the Nevada State Museum) shows ore carts in the mine being loaded from two chutes.

Breaking Up Rocks Underground

The rocks underground were not found in small chunks that could be moved readily. Instead, miners had to drill holes into the rock by hand using a drill bit and a hammer, load the holes with explosive, then shoot off the explosive to crack the rock. The miners then dug (mucked) the broken rock into the ore carts. Later improvements made it so the miners could use drills driven by compressed air to make the holes to be loaded with explosives. The inserted photograph of a painting by T.L. Dawes shows a miner using an early pneumatic drill, the Burleigh drill. (Tingley, Horton, and Lincoln, p. 13; used by permission of the NBMG)

Miners first used black powder as the explosive, but switched to Alfred Nobel's dynamite after its invention in 1866.

Water Removal

Often the mines were wet. This usually didn't mean merely a bit damp, but the lower levels intercepted a water table or aquifer so water flooded the tunnels. That meant that the water had to be removed if men were to mine the rocks. At Virginia City, huge water pumps were employed to keep the water from flooding the mines. To make things more difficult, the water in the mines in Virginia City was hot. Adolph Sutro tried to alleviate the water problem by digging a tunnel from the mines through the mountain to the east into the valley of the Carson River. Unfortunately, by the time his tunnel was built (started in 1869 after aborted proposals in 1866 and completed in 1878), the mines were already deeper than the tunnel so the tunnel did not drain those lower levels of the mines. This diagram (used by permission of the NBMG) shows a cross section of the Sutro Tunnel intersecting the Comstock vein. (Purkey and Garside, p. 62.)

Square Set Timbering

The ore rocks in the Comstock were not found in small veins, but in larger masses of quartz surrunded by a wet, clay-rich material. In order to remove that difficult ore, the miners had to build wooden platforms from wood to replace the ore that was already removed. That held the rock in place so the mine didn't collapse and gave the miners a working surface from which to take out the next layer of ore. This type of support was called square set timbering and was invented in Virginia City by Philipp Deidesheimer in 1860 (see Smith, G.H., Tingley, J.V, The History of the Comstock Lode, NBMG and University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada, 1998).

Getting the wood for this timbering and clean water for the town were two huge obstacles to mining to be overcome. (see Galloway, J.D., NBMG Bulletin B45, Mackay School of Mines, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, 1947.) See also the Environmental Section of this site, Influence of Mining.

Moving the Rocks on the Surface

Once rocks were brought to the surface, miners used gravity whenever possible to move the rocks through the processing. First the rocks were dumped from the bucket into an ore cart on the surface. It may have had to travel on a train before reaching the processing mill, but that added cost to processing the ore. The ore cart took the ore rock to the stamp mill to be crushed before it could be chemically processed. This photograph of a small stamp mill in Virginia City shows the weights on rods that were lifted and dropped (stamped) onto rocks at the bottom of the structure. Then the finely ground rock was fed into the mill, generally by a gravity feed directly from the stamp mill. Then the rock was mixed with other minerals to separate the gold from the rest of the rock (see Ore Processing).

Waste from the ore processing was generally in the form of a water slurry of finely powdered rock. In the days of the Comstock mines, this waste slurry was frequently fed directly into the river, but sometimes it went to a tailings pond to settle and evaporate the water. This photograph of a more modern, though abandoned mill on the Comstock shows a former tailings pond in the center foreground where there is an oval of greener grass and no shrubs.

The products of the mine, mainly silver and gold, were sent to population centers such as San Francisco. The legislation to build the Carson City Mint was passed in 1863, and the mint actually opened in 1869. It was the silver from the nearby Comstock Lode and the increased population that came with the mining operations that made the development of the mint in Carson City favorable.

References

Purkey, B.W. and Garside, L.J., Geologic and Natural History Tours in the Reno Area, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication 19, University of Nevada, 1995

Tingley, J.V., Horton, R.C., and Lincoln, F.C., Outlines of Nevada Mining History, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication 15, University of Nevada, 1993

Smith, G.H., Tingley, J.V, The History of the Comstock Lode, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology and University of Nevada Press, Reno, Nevada, 1998

Galloway, J.D., Early Engineering Works Contributory to the Comstock, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Bulletin 45, University of Nevada, 1947

Home

Home